Massachusetts last year joined six other U.S. states in redefining what is considered domestic violence and extending evidence that can be used to enforce restraining orders against a domestic violence abuser. Three important additions in the new law to the state’s existing domestic violence laws now mean that victims who are not solely the target of physical or sexual violence may now be better protected from actions by their abusers, who in the most part are intimate partners or close family members.

Massachusetts new “Coercive Control” law: An Act to Prevent Abuse and Exploitation

Bill H.4744, “An Act to Prevent Abuse and Exploitation” was signed into law by the state’s Governor, Maura Healey, in September 2024. Three main extensions of previous domestic violence laws were included in the new legislation. These were:

- a definition of coercive control and its inclusion as a form of domestic violence and the implications of this for victims and those who help them;

- making the use of new technology to coerce or harass victims illegal;

- programs used to educate young people about the negative effects and dangers of sexting are to be pursued.

What is coercive control and how does the new legislation define it?

Coercive control as a pattern of behavior is almost always the actions of a spouse or partner in an intimate relationship or a close family member. In most cases, although not all, it is a male abuser who is most likely to be responsible for this type of behavior against a female victim.

The new law defines coercive control as “a pattern of behavior intended to threaten, intimidate, harass, isolate, control, coerce or compel compliance of a family or household member that causes that family or household member to reasonably fear physical harm or have a reduced sense of physical safety or autonomy.”

Examples of behavior regarded by the law as coercive control include the following if they represent an established pattern of behavior:

- compelling the victim to engage in or abstain from specific behaviors or activities;

- controlling, regulating, or monitoring the victim’s activities, communications, movements, finances, economic resources, or access to services including through technology;

- depriving the victim of basic needs;

- intentionally damaging the victim’s property;

- isolating the victim from friends, relatives, and other sources of support;

- repeated unwarranted court actions against the victim;

- threatening cruelty to an animal connected to the victim;

- threatening to harm a child or relative of the victim; and

- threatening to publish the victim’s sensitive personal information, including sexually explicit images.

In addition to the above examples, any single incidence of these following four behaviors may also be regarded as coercive control:

- causing the victim to fear physical harm or have a reduced sense of physical safety or autonomy;

- completed or attempted abuse of an animal connected to the victim;

- harming or attempting to harm a child or relative of the victim; or

- publishing or attempting to publish sexually explicit images of the victim.

Penalties for coercive control

Coercive control by itself is not a crime. A perpetrator who has been exerting coercive control against a victim is not going to be arrested for a crime unless the perpetrator is the subject of a restraining order and continues to exhibit behaviors recognized as coercive control as defined in the new law. The law does now allow a victim of coercive control to apply for a restraining order against that person and that means that the perpetrator can be arrested if he/she continues to persist in coercive control against the victim who is under the protection of the restraining order.

Police may still arrest the perpetrator if it is suspected that part of the behavior exhibited is a misdemeanor a felony. For example, even if there has been no restraining order placed on that perpetrator, if malicious damage is done to property belonging to the victim, then not only may this be evidence used to apply for a restraining order, but it may lead to the perpetrator as well.

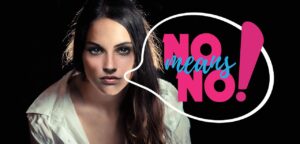

H.4744 and its role in preventing revenge porn and publishing deep fake images

Revenge porn is the use of sexually explicit photos and videos of the victim or purporting to be the victim taken with or without consent and distributed publically in any one of a number of ways, such as on social media. It is recognized that revenge porn is used in conjunction with coercive control to threaten, intimidate or harass the intimate partner or close family member. This form of behavior is punishable if the explicit material was distributed without the subject of the material consenting to it, even if the actual taking of photos or videos was consented. The perpetrator must also be shown to be distributing material with intent to harm the victim and/or recklessly disregard the psychological effect that distribution of material might have on the victim.

Deep fake images are a growing problem as a result of the improvements in artificial intelligence (AI). It has become easier for perpetrators to use AI technology to create and distribute fake sexually explicit images of their victim, for example, inserting the face of the victim on to a nude fake photo of a body. This form of harassment and intimidation is, like revenge porn, now prohibited and punishable if criteria as given above are established.

Sexting education for young people

The third addition to the law intends to educate young people about the effects and dangers of sexting. Sexting is the increasingly common use of sexually explicit text messages sent from one person to another. Sexting may be unsolicited sexually explicit messages in text form or accompanied by images or video content, like the material described above, used to intimidate or harass another person. The prohibition of sexting takes a more nuanced attitude to the offence, aiming to inform young people of the negative effects of this behavior rather than imposing sentences on the perpetrators right away.

For more information, visit our website or contact us for a free initial legal consultation today